On 17 April 2023, a petition [1] was debated in the UK Parliament calling for the Government “to commit to not signing any international treaty on pandemic prevention and preparedness established by the WHO, unless this is approved through a public referendum.” The petition had received 156,086 signatures. Of the thirteen Members of Parliament (MPs) who spoke during the debate [2] four strongly supported the motion, three took a more neutral stance, and six strongly opposed the petition or elements of the argument. Examples of arguments in support of the petition can be viewed in a collation of clips taken from the video of the debate [3].

There was a noticeable contrast between the arguments presented by MPs supporting the petition — who exhibited concern for the constituents who had signed the petition and approached them directly — and those opposing it. All those who, like the petitioners, were concerned about the growing power and influence of WHO and threats to national sovereignty were familiar with the contents of the so-called ‘pandemic treaty’ [4], since labelled the WHO CA+, as well as proposed amendments to the International Health Regulations (IHR) [5]. While some opposing the petition were also familiar with the document, others had not even read it, prompting Andrew Bridgen (MP for North West Leicestershire) to plead with members to do so.

Those concerned about these proposals presented well-reasoned arguments reflecting an understanding of the history of WHO [6], its many failures during Covid-19, and its current problematic relationships with non-state funders [7,8]. Those supporting WHO’s proposals uncritically supported WHO, focusing on its public health successes and ignoring obvious concerns. Perturbed by the lack of parliamentary scrutiny of the Covid response measures, some MPs worried that the UK government, having played a leadership role in drafting the treaty, might ratify it without parliamentary debate. This reservation was flatly denied by those opposing the petition, with some denying that WHO would in any way threaten UK sovereignty, that its role would remain advisory in nature, and that those opposing the treaty were in effect opposing international cooperation.

This article analyses the arguments made by those rejecting the petition, drawing on insights from Behavioural Science. During the debate, these MPs tended to rely on the following tactics:

- Using derogatory language or false claims to discredit speakers and their arguments

- Making inaccurate and unsubstantiated statements

- Using globalist slogans

- Patronising the petitioners

- Using the debate as an opportunity for party-political point-scoring

- Downplaying or normalising threats to sovereignty

- Promoting internationalism over sovereignty.

The debate was a sad reminder that it is not necessarily the quality of arguments, or even the sincerity of the individuals making them, that wins the day.

MPs have a duty of care to their constituents to ensure that they are as knowledgeable as possible about the issue being debated, and that they consider the facts rationally and honestly; and citizens deserve to have their concerns taken seriously.

1. Using derogatory language and labels to discredit speakers and their arguments

A tactic used to shut down discussion and debate was to attach derogatory labels to those supporting the petition. In the debate, two such labels used in relation to the Covid event and the pandemic treaty were ‘conspiracy theory/theorist’ (ten references made by four speakers) and ‘anti-vax’ (one speaker). Some opposing the petition used these labels early in their presentations, their comments and tone indicating that these were untenable positions that no sane person could possibly subscribe to.

Using such labels at the beginning of the debate set the scene, immediately employing a behavioural science tactic to prime the participants and the wider audience. Priming is a ‘nudge’ [9] tactic; techniques that are used to modify people’s behaviours or emotions in a way that is unconscious and therefore difficult to identify or counter. Priming [10] occurs when the emotional attachment or views held about one issue are then used to influence the emotional attachment on a separate and unrelated issue; an emotional contagion if you like. This can be utilised to produce a positive or negative relationship. Over the past three years in particular, the phrase ‘conspiracy theorist’ has become strongly and negatively associated with an archetype of someone whose views are not based in fact and who are not community minded, and therefore not socially acceptable. By stating in his introductory comments that “I have no time for conspiracy theories”, leader of the debate Nick Fletcher (MP for Don Valley) activated this already negative mental construct and associated it with the question of the WHO pandemic treaty. Whether this was purposeful or not is debatable but concerns about conspiracies do seem strangely placed in a debate which should be about publicly documented proposals, and UK and international legislation.

Similarly, Sally-Ann Hart (MP for Hastings and Rye), who herself was committed to representing the concerns of constituents who had signed the petition, warned that, “We must be wary of … conspiracy theories distorting the facts and scaring people. Transparency of debate is therefore needed to squash those conspiracy theories.”

Some comments could only be described as invective. Language such as that used by John Spellar (MP for Warley) was entirely inappropriate in the context of a Parliamentary debate:

… the poisonous cesspit of the right-wing conspiracy theorist ecosystem in the United States … an appalling subculture of those who live by conspiracy theories … Unfortunately, we have some people — a very limited number … who wallow in the realm of conspiracy theories.

The ‘conspiracy theorist’ label has become a catch-all term used to discredit numerous perspectives that disagree with the dominant narrative. It has also taken on the power of a curse, which those who hope to remain accepted by their peers must protect themselves from by declaring their immunity.

Another such label is ‘anti-vax’, used by Mr Spellar who interjected early in Mr Fletcher’s introduction:

I thank the hon. Gentleman … for highlighting both smallpox and polio. Is the fact of the matter not that it has been a worldwide vaccination programme that has enabled us to achieve that? Does that not demonstrate the falseness of the anti-vax campaigns?

This is another example of priming, where an exceptionally negative construct (anti-vax), which was set up in mainstream and social media over the past few years, is associated with those who may have genuine concerns about the powers being delegated to a non-elected body. When attached to a person, the related term ‘anti-vaxxer’ is an example of an ad hominem attack [11], which is an example of a false argument. Instead of the argument being discussed on its own merit in terms of data or facts, the audience and other participants are misdirected toward a perceived ‘failing of character’ in those who might have a different view and legitimate questions.

Mr Spellar used this terminology to discredit those wary of vaccinations, in particular the Covid-19 genetic therapy. He continued his interruption of Mr Fletcher’s introductory remarks with the following tirade against academic gastroenterologist Dr Andrew Wakefield who, in 1998, co-authored a research study in The Lancet, linking inflammatory bowel symptoms in 12 autistic children to the Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) vaccine:

Part of this argument has been about vaccination. We go back to Dr Wakefield and that appalling piece of chicanery that was the supposed impact of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, which has now been completely exposed and discredited. Indeed Mr Wakefield is now no longer a recognised doctor.

This argument is an example of ‘false equivalence’ [12], another propaganda tool that has the effect of misdirecting the audience away from the key facts of the debate. Those who doubt the safety and efficacy of the novel Covid ‘vaccine’ have not necessarily questioned the safety and efficacy of all other vaccines, and should therefore not be considered ‘anti-vaxxers’. By associating arguments against the Covid shot with the MMR vaccine debacle, the purpose is to tar objections to this entirely novel and inadequately tested therapy with the same brush as arguments levied against an earlier, unrelated, conventional vaccine.

Mr Spellar’s interjection also reflects another tactic of those who wish to quash debate, namely the use of threats to intimidate those who might be inclined to consider alternative narratives. The story of the suppression of harms caused by the MMR vaccine has much in common with the current censorship of reports of serious adverse events and deaths following the Covid injections. Raising the 25-year-old case of Dr Wakefield who is “no longer a recognised doctor” represents a threat, already a reality for many ethical doctors and scientists, that those who speak out against the harms caused by the Covid injections face being dismissed and deregistered.

2. Using inaccurate and unsubstantiated statements

Justin Madders (MP for Ellesmere Port and Neston) also used derogatory language in denying concerns about threats to national sovereignty posed by global organisations such as WHO:

On the absurd side, a narrative has been created that the World Health Organization is a body intent on world domination. Borrowing tropes from conspiracy theories, I found one website referring to the WHO as ‘globalists’ … That sentiment is clearly ludicrous, as is the reference to the WHO being owned by Bill Gates or the Chinese Government.

The treaty has nothing to do with Bill Gates, and it is not the first step in creating a world-dominating authoritarian state.

The first sentence in the quote above is an example of a behavioural science nudge tactic called ‘framing’. In framing, words, metaphors and perspectives are used in a way that makes the message more attractive and activates certain emotional reactions. The image created by the MP’s statements is quick to evoke a mental picture of a film-like villain plotting to take over the world. Being ‘absurd’ (untrue) and a ‘narrative’ (story), this should clearly be discounted.

Beyond the language used, Mr Madders’s claims are not substantiated and as such are simply opinions. Firstly, as the United Nations (UN) agency responsible for global public health, WHO can indeed be considered a ‘globalist’ organisation, along with numerous other international bodies such as other UN agencies, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, the World Economic Forum (WEF), and international corporations and foundations. But, largely due to the growing influence exerted over national governments by WHO and other unelected supra-national bodies during Covid, the term ‘globalist’ has taken on more sinister connotations. Its use by those critical of the dominant narrative may account for Mr Madders treating the term as a ‘red flag’.

Secondly, Mr Madders may be unaware of the significant changes to WHO’s funding model that have taken place in recent years, with assessed contributions [13] from Member States having declined to less than 20% of WHO’s financing, and Bill Gates now being one of its major funders. WHO’s own website records that, as of Quarter 4 of 2021, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) was their second-largest donor (9.49%) after Germany [14]. While on this point, Steve Brine (MP for Winchester) asserted that “the UK is the second-largest contributor to the WHO”, which is incorrect; in fact, the UK is the sixth-largest contributor (5.99%). Gates is also a founding partner and second-largest contributor to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which is the fifth-largest funder of WHO (6.43%). And with 56.14% of BMGF’s funding going to support WHO’s Headquarters [15], it is unlikely that “The treaty has nothing to do with Bill Gates”, as asserted by Mr Madders.

Many unsubstantiated statements regarding Covid ‘vaccine’ safety and effectiveness were also made during the debate. Anne-Marie Trevelyan (Minister of State, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office) asserted that “AstraZeneca saved lives worldwide”, despite the use of this adenovirus viral vector vaccine being restricted or suspended in numerous countries due to many reports of recipients suffering blood clots [16].

Similarly, Mr Spellar, referring to the Pfizer mRNA ‘vaccines’, stated that it “certainly was not unproven or unsafe, and it had a huge beneficial impact across the world.” There is, in fact, mounting evidence showing that the Covid injections, released under emergency use authorisation before adequate testing could be undertaken, have been neither safe nor very effective. All vaccine adverse events tracking systems, including the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Yellow Card system in the United Kingdom, the European Medicines Agency’s EudraVigilance system in the European Union, and the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) in the United States, have recorded unprecedented numbers of serious adverse reactions, including deaths. Furthermore, an increasing number of studies are reporting evidence of a broad range of serious adverse events [17]. An independent systematic review of serious harms of the Covid-19 vaccines, currently in pre-print, adds significant weight to these findings [18].

Furthermore, after a group of scientists and medical researchers successfully sued the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) [19] to release many thousands of documents related to licensing of the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine, it was revealed that early trials had resulted in hundreds of adverse reactions [20 (Appendix 1)]. This information had been withheld from the public by the authorities.

The injections have also been been unable to stop SARS-CoV-2 infection or transmission, with Dr Peter Marks of the FDA admitting in a letter responding to a citizens’ petition that proof of efficacy had not been required for authorisation [21]:

It is important to note that FDA’s authorization and licensure standards for vaccines do not require demonstration of the prevention of infection or transmission. (p.11)

Furthermore, the applicable statutory standards for licensure and authorization of vaccines do not require that the primary objective of efficacy trials be a demonstration of reduction in person-to-person transmission. (p.13)

In addition, there is growing concern that claims that the boosters prevent severe illness and deaths amount to a “wishful myth” [22].

Three years of pro-vaccine propaganda and ongoing efforts to censor reports of vaccine harms have effectively blinded many people to the possibility that the rollout of Covid injections may be related to the sharp rise in excess deaths now being experienced in many countries [23; 24]. This is despite the fact that many vulnerable people, such as the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities, had died previously as a result of Covid-19, lockdown measures and medical interventions.

Despite having had the opportunity to peruse the evidence presented by the petitioners, Mr Spellar was still sure that the vaccination campaign had been a huge success, stating:

… mobilisation of [the] intellectual power and production capacity [of the major pharmaceutical companies] in producing a vaccine in record time to stem the tide of covid was absolutely magnificent.

3. Using globalist slogans

Just as certain terms (conspiracy theorist, anti-vaxxer) have become modern-day curses causing those so labelled to be socially shunned, so have other terms and slogans become the mantras of those wishing to demonstrate their membership of the mainstream. These catchy but often meaningless slogans are building blocks of a collective reality, introduced and normalised through the presentations, publications and public relations communications of powerful individuals, and globalist organisations such as the UN, WHO, WEF and BMGF.

Mr Madders, for example, echoed Bill Gates [25] when he stated: “We need to be better prepared for the next pandemic.” This also represents an unsubstantiated claim, as it ignores the reality that pandemics are actually extremely rare. Since 1900, only five pandemics, each responsible for over one million deaths, have broken out, namely the Spanish flu (1918-1920), the 1957-1958 influenza pandemic, the Hong Kong flu (1968-1969), the AIDS pandemic (ongoing since 1981), and Covid-19 [26]. It also powerfully illustrates the effectiveness of presupposition, where the speaker inserts a statement or assumption as a fact agreed by all and therefore requiring no evidence of its own. The phrase “the next pandemic” provides a nudge by inserting itself unconsciously into the psyche of the listener and readily bypassing the conscious thought process [27].

The Covid event did, however, demonstrate that a pandemic can mean big gains for certain people. It can literally be used to “reset our world” [28], creating unprecedented numbers of billionaires while destroying the lives of billions or others, stripping citizens of their rights and freedoms, unleashing a tyrannical and repressive security apparatus, and creating a ‘polycrisis’ [29], in response to which governments and even citizens will beg for unprecedented levels of global control.

One of the most meaningless slogans, which appears to have been invented by the UN at the beginning of the Covid event, and which has become a mantra reiterated by countless organisations and individuals, is ‘nobody is safe until everyone is safe’. It is not clear what this unsubstantiated statement even means, but what is clear is that it is demonstrably untrue. Nonetheless, this mantra was recited in some form by four speakers, with Anne McLaughlin (MP for Glasgow North East) stating, “It is only when the world is safe from Covid-19 that any of us are truly safe.”

Not only does such an obvious fallacy, a propaganda trope, have no place in a parliamentary debate, its use as some type of rational fact by four MPs across the political spectrum does bring into question the quality and independence of any literature provided to them ahead of this event. It is worth considering this much-used slogan and its ramifications in terms of any safety incident. The ideology underpinning it is one of collectivism, even socialism, in that the individual and their relative safety is merely incidental compared to the safety of all. Some might argue that this contradicts the fundamental principles of the International Declaration of Human Rights, which puts the individual at its core. Certainly, it is not an idle statement and reflects the underlying changes being proposed by WHO, which is seeking under their ‘One Health’ initiative [30] a more far-reaching remit where ‘everyone’ will include not only all sovereign citizens of participating nations, but animals and the environment as well.

Slogans infuse documents produced by UN agencies such as WHO. In referring to the zero-draft of the Pandemic Treaty, Preet Kaur Gill (MP for Birmingham, Edgbaston) used a number of them, including: ‘leave no country behind’, ‘global health is local health’, ‘we are stronger together’, and ‘vaccine equity’. Trotting out vacuous statements like this might be appropriate at a protest rally but should have no place in a parliamentary debate. Slogans are rallying cries. They are right-sounding and apparently well-meaning, even moral, in nature. Their repetition is quite hypnotic and they seem to act as spells, potentially binding those who faithfully recite them to an outcome they may live to regret [31].

The repetitive nature of any phrase or slogan is a tool of both behavioural science and propaganda. Both the repetitive effect and the rhythmic phrasing allow such phrases to easily enter the unconscious. Over time we simply accept the statement as true, as it bypasses our conscious thought processes that might critically assess such a phrase and see it as false or simply nonsensical. The use of such tactics, particularly by people in positions of authority or trust, allow the effect to be amplified. This is known as the ‘messenger effect’. Simply put, we are more likely to trust the message because it was issued by someone representing expertise and trust [32].

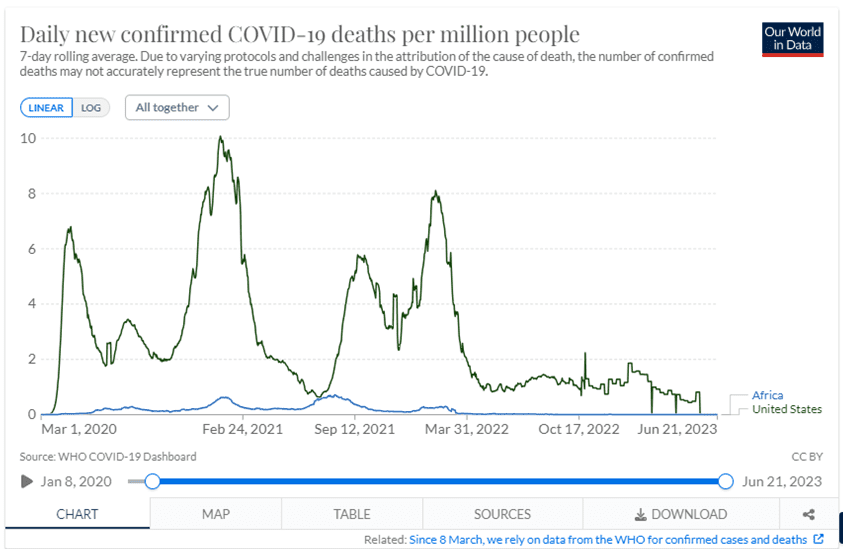

One such case relates to the slogan ‘vaccine equity’. Referring to the “terrible divide in coverage between richer countries and the global south,” Ms Gill lamented that “just 27% of people in low-income countries have received a first dose of a Covid vaccine.” What she does not go on to say, disappointingly, is that there was no correlation between high vaccination rates and low death rates from Covid-19. Indeed, some low-income countries (especially in Africa) with young populations and low vaccination rates experienced very low death rates due to Covid-19, while the USA, one of the richest and most highly vaccinated countries in the world, had one of the highest Covid-19 death rates [33].

4. Patronising the petitioners

Regarding the aim of the petition, which was to request that a referendum be held before the Government could agree to signing the pandemic treaty, Mr Fletcher declared:

Referendums are divisive; they polarise positions and leave a lasting legacy of division. Whether a referendum is appropriate is for the Government to decide, and if they think it is, they must make all the facts known. I suggest that petitioners, while playing their part in the education process, must do so in a sensible manner.

The patronising tone of this comment is ironic. While the referendum on Brexit did indeed sharpen the edge between ‘Leavers’ and ‘Remainers’, the UK Government’s Covid-19 response was possibly even more effective at dividing the populace into camps and pitting one side (those who complied with the mandates) against the other (those who chose not to comply). Furthermore, insisting that citizens should be “sensible” ignores the fact that constituents in favour of a referendum contacted their MPs to raise thoughtful, well-researched concerns, while some MPs arguing against the referendum tended to rely on slogans, unfounded generalities, and invective, rather than “sensible”, factual, reasoned arguments.

Mr Spellar not only used disparaging language to deny the request for a referendum, but also predicted that it would be rejected by the House:

We cannot be arguing to have [a referendum] for every bloomin’ issue, every policy and every treaty. … What we are seeing is overreaction and hysteria, and I would argue that we should give the petition a firm rejection, as I am sure we would do if it ever came to the Floor of the House of Commons.

Inasmuch as MPs in the UK are supposed to represent and take seriously the concerns of their constituencies, it is disturbing that an elected Member should respond with such contempt to a petition signed by more than 150,000 people.

5. Party-political point-scoring

Disappointingly, despite the importance of the debate and the number of citizens who had taken the time to express their concerns about the pandemic treaty, Ms McLaughlin and Ms Gill spent much of their time criticising the Conservative Government’s response to the Covid event. Instead of focusing on the debate, they chose to score party-political points by indicating the readiness of the Scottish National Party and Labour Party to implement WHO’s agenda, including enabling vaccine equity; sharing technology, knowledge, and skills; and strengthening global health systems using, ironically, the failing National Health Service as a model.

6. Downplaying or normalising threats to sovereignty

The Covid-19 event has been a classic case of the popular dialectic of ‘Problem-Reaction-Solution’. The engineered over-reaction to the problem of Covid-19 (whether or not there was an engineered virus), and the subsequent societal fall-out, have left traumatised people and their governments desperate to be better prepared for the much-anticipated ‘next one’, and ready to accept a ‘solution’ that few would have countenanced just four years ago.

In her presentation, Ms Gill expressed the need for an international approach to tackle transnational threats and improve global public health:

Negotiating an effective international treaty on pandemic preparedness is an historic task, but, if we can achieve it, it will save hundreds of thousands of lives.

If we can use the WHO to support basic universal healthcare around the world, infectious diseases are less likely to spread and fuel global pandemics.

It is through multilateral efforts, strengthened through international law, that we can ensure that the response to the next pandemic is faster and more effective, and does not leave other countries behind.

… the Opposition absolutely support the principle of a legally binding WHO treaty that sets the standard for all countries to contribute to global health security.

We need a binding, enforceable investment and trade agreement among all participating countries to govern the coordination of supplies and the financing of production, to prevent hoarding of materials and equipment, and to centrally manage the production and distribution process for maximum efficiency and output in the wake of a pandemic being declared.

The last few comments point to one of the most worrying issues for those concerned about sovereignty: if accepted, the pandemic treaty and amendments to the IHR would no longer be non-binding recommendations subject to government oversight but would become legally binding. WHO would be given legislative powers to mandate medical and non-pharmaceutical interventions; to commandeer intellectual property, production capability and resources; and to sanction those who refused to comply.

Some MPs downplayed concerns about these threats to national sovereignty. Mr Madders stated that “creating a global treaty [was] entirely reasonable and responsible” and that it was possible to “both protect our values of freedom and democracy and work more closely with other countries in the face of a global threat.”

Mr Spellar agreed, noting that they were “signatories to hundreds of treaties around the world” and that signing trade treaties was “part of engaging with the world.” He added that during Covid, “international scientific cooperation” had “enabled us to produce a vaccine within something like twelve months instead of the normal ten years … [thus] stabilising the situation.” What was not mentioned is that it was not primarily international collaboration among scientists that allowed the rapid deployment of these Covid-19 countermeasures, but the institution of emergency use authorisations, which allowed inadequately tested products to be dispensed worldwide. Far from “stabilising the situation”, these injectables continue to cause unprecedented numbers of adverse events and deaths, resulting in ongoing destabilisation of society post-Covid.

Steve Brine (MP for Winchester) observed that, “We cede sovereignty through membership of organisations. We cede the sovereignty to go to war by being a member of NATO.” It is true that all manner of treaties exist between countries and that these are essential for international cooperation; but cooperating as sovereign nations is entirely different to taking instructions from an unelected, supra-national body that is unaccountable to populations. Once in place, WHO’s pandemic treaty and the amendments to the IHR threaten to reduce national sovereignty, giving full power to WHO and its director-general to call pandemics and health emergencies and to regulate the responses of member states.

Those in favour of the pandemic treaty provided no evidence that a one-size-fits-all, legally mandated response to future pandemics would actually prove effective. In fact, Covid-19 was an object lesson in the foolishness of imposing the same public health ‘solutions’ on radically different nations and communities. In reality, mandating centralised protocols disrespects human rights, cultural diversity, national sovereignty, the scientific method, and innovation in healthcare. Instead of trusting human ingenuity to create a multitude of locally appropriate responses, it increases the risk of spectacular failure should the single global solution prove ineffective.

In an attempt to counter fears about a loss of sovereignty, Mr Madders stated that “We live in a liberal democracy and … are determined to keep it that way.” He denied people’s:

fears that the treaty will restrict freedom of speech to the extent that dissenters could be imprisoned, that it will impose instruments that impede on our daily life, and that it will institute widespread global surveillance without warning and without the consent of world leaders … [and that] Under this treaty, those things will apparently be done without our Government having a say.

He did, however, acknowledge that the measures mentioned above were “already in the power of the Government under the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984.” Referring, without giving any details, to “fact checkers” and an unnamed “WHO spokesperson”, he reassured citizens that “WHO would have no capacity to force members to comply with public health measures.” The tyrannical actions during Covid of governments worldwide against their own citizens — many of whom assumed that they did, in fact, live in a “liberal democracy” — makes one wonder why these governments would behave any more independently in future, especially if legally required to follow WHO’s dictates. The repressive regulations and laws passed in various countries since 2020 suggest that this is unlikely, as governments seem to have become addicted to the sweeping emergency powers granted them by this convenient global ‘pandemic’.

Mr Madders and Ms Gill also attempted to allay citizens’ fears by pointing out that there was “over a year of negotiations to go” and that the treaty “would still have to be ratified by the United Kingdom”. Ms Gill also commented that:

The draft treaty is primarily about transparency, fostering international cooperation, and strengthening global health systems … the very first statement in the zero draft text reaffirms “the principle of sovereignty of States Parties” [and that] the implementation of the regulations “shall be with full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons.”

Noting the dismissive attitude of the majority of MPs to the petitioners’ concerns, there is little chance that another year of negotiations will convince the UK Government to reject the treaty.

7. Promoting internationalism over sovereignty

The UK, as an erstwhile imperial and colonial power, continues to play a leadership role internationally. This may be why some MPs, such as Ms McLaughlin, could not believe that WHO might threaten UK’s sovereignty:

The treaty would have absolutely no effect whatsoever on the UK’s constitutional function and sovereignty … [Imagine a] terrible situation whereby the UK might be unable to make its own decisions if it is outvoted by other countries … the UK is a leading member of the WHO and a primary architect of the treaty, so that is not what is happening here.

Anne-Marie Trevelyan (Minister of State, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office) also stressed that the UK was:

a sovereign state in control of whether we enter into international agreements … with its voice, expertise and wisdom, and our trusted partner status with so many other member states in the UN family, [it] is respected and listened to.

Ms Trevelyan also referred to the UK’s role as “a global leader, working with CEPI, Gavi and the WHO,” stating that she was “proud to lead the fundraising for Gavi and COVAX.”

A deep chasm appears to have formed between the UK Government and its people. The discussions during this debate suggest that a minority of MPs [3] [link to PANDA video] view themselves as representatives whose duty it is to serve their constituents and respond to their concerns. Most, however, appear to have shifted their focus and allegiance to the international sphere, identifying as members of the “UN family”, playing a leading role in developing WHO’s pandemic instruments, and raising funds, which will ultimately benefit vaccine manufacturers and their investors, impoverishing the majority in the process. Under these circumstances, it is clear why Parliament is unwilling to risk a referendum on WHO’s Pandemic Treaty. There are just too many globalist interests at stake.

At home, increasing numbers of UK citizens are growing weary of a government that speaks glibly of ‘no country left behind’, while leaving its own nation in the dust. Where the people are concerned, trust is gone.

As Danny Kruger (MP for Devizes) warned:

At the moment, we do not have a commitment from the Government that they would bring the proposals to Parliament, which is very concerning. They say that in our interconnected world we need less sovereignty and more co-operation, which means more power for people who sit above the nation states. I say that in the modern world we need nation states more than ever, because only nation states can be accountable to the people, as the WHO is not.

Concluding comments

After two-and-a-quarter hours of deliberation, Mr Fletcher concluded the debate by thanking the Minister for assuring Members that UK sovereignty was not at risk, and then delivering the most inconclusive resolution:

That this House has considered e-petition 614335, relating to an international agreement on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

For the 156,086 citizens and their representatives who had made the effort to engage Parliament thoughtfully and actively using the relevant democratic process, this ‘resolution’ resolved nothing at all. The exercise amounted to all form and no substance; not only were requests for a referendum dismissed out of hand without adequate discussion, but there were indications that the matter might not even be discussed in the House of Commons.

Illustrating just how little impact was made by those representing the petitioners despite the strength of their arguments, subsequent to the debate and in response to this petition, the government’s official response published on their website [1] commenced with the words:

To protect lives, the economy and future generations from future pandemics, the UK government supports a new legally-binding instrument to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

This ominous response was followed by the now familiar slogan that would sit comfortably in the pages of Orwell’s 1984 but has no place in an official government statement: “Covid-19 has demonstrated that no-one is safe until we are all safe.” Its use further erodes the expectations that such debates will be carried out without bias, undue influence, or ignorance.

MPs have a duty of care to their constituents to ensure that they are as knowledgeable as possible about the issue being debated, and that they consider the facts rationally and honestly; and citizens deserve to have their concerns taken seriously. Yet two critical questions remain unanswered: firstly, having explicitly stated their support for WHO’s pandemic instruments, will the UK Government bring this matter to Parliament to be debated? And secondly, would agreement with these instruments, ‘in effect’ if not legally, mean the relinquishment of sovereignty? After all, if the only way the UK will be able to make a sovereign decision in future is by removing itself from membership of WHO, then why would the country wish to sign this treaty in the first place?

References

- UK Government and Parliament, Petition: ‘Do Not Sign Any WHO Pandemic Treaty Unless It is Approved Via Public Referendum’, (Debated 17 April 2023) <https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/614335> [accessed 15 June 2023]

- parliamentlive.tv, ‘Video Recording of Westminster Hall Debate: e-petition 614335, Relating to an International Agreement on Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response’, (17 April 2023) <https://parliamentlive.tv/Event/Index/d667d23f-1bd5-4c71-8237-3dd240de0651> [accessed 25 June 2023]

- PANDA Video

- World Health Organization, ‘Bureau’s text of the WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response (WHO CA+)’, (2 June 2023) <https://apps.who.int/gb/inb/pdf_files/inb5/A_INB5_6-en.pdf> [accessed 25 June 2023]

- World Health Organization, ‘Article-by-Article Compilation of Proposed Amendments to the International Health Regulations (2005) submitted in accordance with decision WHA75(9)’, (2022), <https://apps.who.int/gb/wgihr/index.html> [accessed 25 June 2023]

- David Bell, ‘The World Health Organization and COVID-19: Re-establishing Colonialism in Public Health’ Panda, (5 July 2021) <https://pandata.org/who-and-covid-19-re-establishing-colonialism-in-public-health/> [accessed 29 June 2023]

- David Bell, ‘International Health Regulations and Pandemic Treaties – What is the Deal?’ Panda, (19 May 2022), <https://pandata.org/international-health-regulations-and-pandemic-treaties-what-is-the-deal/> [accessed 28 June 2023]

- David Bell, ‘The Myths of Pandemic Preparedness’, Panda, (29 November 2022), <https://pandata.org/the-myths-of-pandemic-preparedness/> [accessed 28 June 2023]

- Richard Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008)

- Psychology Today, ‘Priming’, <https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/priming> [accessed 29 June 2023]

- Pierpaolo Goffredo, Shohreh Haddadan, Vorakit Vorakitphan, Elena Cabrio and Serena Villata, ‘Fallacious Argument Classification in Political Debates’, Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-22), (2022) 4143-4149 <https://www.ijcai.org/proceedings/2022/0575.pdf>

- Stephanie Sarkis, ‘This is Not Equal to That: How False Equivalence Clouds our Judgment’, Forbes, (19 May 2019) <https://www.forbes.com/sites/stephaniesarkis/2019/05/19/this-is-not-equal-to-that-how-false-equivalence-clouds-our-judgment/?sh=569a0b335c0f> [accessed 29 June 2023]

- World Health Organization, ‘Assessed Contributions’ <https://www.who.int/about/funding/assessed-contributions> [accessed 15 June 2023]

- World Health Organization, ‘Contributors’ <https://open.who.int/2020-21/contributors/contributor> [accessed 15 June 2023]

- World Health Organization, ‘Contributor: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’ <https://open.who.int/2020-21/contributors/contributor?name=Bill%20%26%20Melinda%20Gates%20Foundation> [accessed 15 June 2023]

- Reuters, ‘All the Countries That Restricted or Suspended Use of AstraZeneca and J&J Covid-19 Vaccines’, IOL, (24 April 2021), <https://www.iol.co.za/news/world/all-the-countries-that-restricted-or-suspended-use-of-astrazeneca-and-j-and-j-covid-19-vaccines-15e22cb0-3fef-4dab-9176-ebb7862fa6bb> [accessed 25 June 2023]

- Joseph Fraiman, Juan Erviti, Mark Jones, Sander Greenland, Patrick Whelan, Robert M Kaplan and Peter Doshi, ‘Serious Adverse Events of Special Interest Following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination in Randomized Trials in Adults’, Vaccine 40 (2022), 5798-5805 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.08.036>

- Peter Gøtzsche and Maryanne Demasi, ‘Serious Harms of the COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review’, Preprint with medRxiv, (2023) <https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.06.22283145>

- United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas Fort Worth Division, ‘Case 4:21-cv-01058-P Document 35’, (Filed 6 January 2022), <https://www.scribd.com/document/551589334/FDA-Foia-Request-010722#> [accessed 26 June 2023]

- Worldwide Safety Pfizer, ‘5.3.6 Cumulative Analysis of Post-Authorization Adverse Event Reports of PF-07302048 (BNT162B2)’, (Received 28 February 2021, Approved 30 April 2021), <https://phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/5.3.6-postmarketing-experience.pdf> (Appendix 1) [accessed 26 June 2023]

- Peter Marks (Director, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, FDA), Letter sent to Linda Wastila, Coalition Advocating for Adequately Labeled Medicines (CAALM), Re: Citizen Petition, Docket Number: FDA-2023-P-0360, (18 April 2023), <https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23786932-fda-letter-on-covid-19-vaccine-labeling> [accessed 18 June 2023]

- Yaakov Ophir, Yaffa Shir-Raz, Shay Zakov and Peter A. McCullough, ‘The Efficacy of COVID-19 Vaccine Boosters against Severe Illness and Deaths: Scientific Fact or Wishful Myth?’ Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons, 28(1) (2023), 20-27 <https://jpands.org/vol28no1/ophir.pdf> [accessed 25 June 2023]

- Thomas Fazi and Toby Green, ‘Why Are Excess Deaths Still So High? We Can’t Just Blame a Failing NHS’, Unherd, (30 January 2023) <https://unherd.com/2023/01/why-are-excess-deaths-still-so-high/> [accessed 25 June 2023]

- Martin Neil and Norman Fenton, ‘The Devil’s Advocate: An Exploratory Analysis of 2022 Excess Mortality’, Where are the Numbers? (14 December 2022), <https://wherearethenumbers.substack.com/p/the-devils-advocate-an-exploratory> [accessed 27 June 2023]

- Bill Gates, Bill and Melinda Gates on Preparing for the Next Pandemic, online video recording, YouTube, 10 January 2013, <https://youtu.be/Wn0xzZH1dJA> [accessed 18 June 2023].

- David Bell, ‘The Myths of Pandemic Preparedness’, Panda, (29 November 2022) <https://pandata.org/the-myths-of-pandemic-preparedness/> [accessed 27 June 2023]

- Andrew Mullen, ‘The Propaganda Model after 20 Years: Interview with Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky’, Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 6(2) (2017), 12-22 <https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.121>

- Klaus Schwab, ‘Now is the Time For a “Great Reset”’, World Economic Forum, (3 June 2022) <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/now-is-the-time-for-a-great-reset/> [accessed 26 June 2023]

- Simon Torkington, ‘We’re On the Brink of a “Polycrisis” – How Worried Should We Be?’ World Economic Forum, (23 June 2020) <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/polycrisis-global-risks-report-cost-of-living/> [accessed 26 June 2023]

- World Health Organization, ‘One Health’, (21 September 2017) <https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/one-health> [accessed 15 June 2023]

- John T. Cacioppo and Richard E. Petty, ‘Effects of Message Repetition and Negativity on Credibility Judgments and Political Attitudes’, Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 10(1) (1989), 3-12 <https://richardepetty.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1989-basp-cacioppopetty.pdf>

- Christopher J. Anderson and Sara B. Hobolt, ‘Creating Compliance in Crisis: Messages, Messengers, and Masking up in Britain’, West European Politics, 46(2) (2023) 300-323 <https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2091863> [accessed 29 June 2023]

- Edouard Mathieu, Hannah Ritchie, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, Joe Hasell, Bobbie Macdonald, Saloni Dattani, Diana Beltekian, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser ‘Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)’. Published online at OurWorldInData.org, (2020) <https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths> [accessed 25 June 2023]

Sinead Stringer,

Dr David Bell

David is a clinical and public health physician with a PhD in population health and background in internal medicine, modelling and epidemiology of infectious disease. Previously, he was Director of the Global Health Technologies at Intellectual Ventures Global Good Fund in the USA, Programme Head for Malaria and Acute Febrile Disease at FIND in Geneva, and coordinating malaria diagnostics strategy with the World Health Organization.